The History of Taiji

History and tradition in Japan's "whaling town"

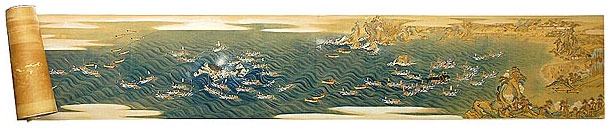

A "maki-e" scroll depicting the traditional whale hunt.

Taiji has been labeled "the small town with a big secret." Not so secret anymore, not since The Cove won an Oscar and focused world attention on this remote coastal town. But what kind of place is Taiji-cho, to give it its proper Japanese name?

It is located near the bottom of the Kii peninsula, almost at the southernmost point of the main Japanese island of Honshu, Taiji is hemmed in by mountains and has traditionally always looked to the sea for its livelihood. It may be a pretty remote place - it takes several hours by train from major cities like Osaka or Nagoya - but the scenic trip to get there is worth it. It is home to some beautiful coastline and is next door to Nachi-no-Taki, the tallest and one of the most spectacular waterfalls in Japan.

The nearby resort town of Kii-Katsuura has some excellent hotels and onsens (hot spring spas), but the people there tend to have a certain ambivalence toward their neighbors down the road. The main reason, other than the universal inter-town rivalry, seems to be the difference in their major industries - while Kii-Katsuura is an important tuna fishing port, Taiji is refered to as Japan's "whaling town" and of course more recently has become infamous for its "oikomi" (drive fishery) form of dolphin hunting. While the last few decades have seen huge numbers of towns and villages merging all across Japan, Taiji has remained proudly independent since 1889, and is the smallest local government by area in Wakayama prefecture. A proposed merger with the surrounding Nachi-Katsuura and several other municipalities was rejected in 2008.

The "Kujira Matsuri" or Whale Festival in Taiji

Taiji and modern whaling

The turn of the 20th century saw the arrival in Taiji of western technology and even a small warship, the spoils of Japan's naval victory over the Russians. Whaling boomed once again in Taiji, and men from the town made up a large part of the crews that fished the waters of the Antarctic in the coming decades. After World War II, due to extensive food shortages, it was the U.S. occupational forces under Gen. Douglas MacArthur who helped promote whaling as an important part of Japan's food supply. So it was that a generation of children across the country ate whale meat as part of their school lunches. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) was set up in 1946 in order to "provide for the proper conservation of whale stocks and thus make possible the orderly development of the whaling industry."

Things began to change with the growth of the environmental movement in the 1970s and increased public concern about the possible extinction of many whale species. While the Japanese were relative newcomers to large-scale fishing in international waters, they were by this point one of the major whaling nations and one of the industry's satunchest defenders. When the IWC's focus switched to one of whale preservation - in 1982 it proposed a moratorium on commercial whaling (enforced from 1986) and in 1994 created the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary - Japan was one of the most vocal opponents of the changes, and was the only country to vote against the snactuary. Along with Iceland and Norway, Japan has continued annual killing of whales, though it is the only nation that justifies it in the name of "scientific research" (the Japanese public broadcaster NHK has a policy of never referring to Japan's whaling without that term as a prefix). Carried out under the Institute of Cetacean Research, this is widely regarded as a "front," as whale meat continues to be sold in Japan. DNA testing has shown that whale meat from Japan is also ending up outside the country.

The older fishermen of Taiji relate tales of their exploits hunting whales in the Antarctic and some Taiji natives are no doubt still involved in the whaling industry. The town's whale museum, whale hunting museum and the two major festivals revolve around the traditions of whaling (photo, above) though the disparity between the traditional form of hunting celebrated during these events and the high-tech version of today is clear to see. And in recent years it has been dolphins, porpoises and small whales that have fallen victims to that technology. The main reason for this is that small cetaceans are not protected by the IWC moratorium, so when commercial whaling stopped the numbers of smaller sea mammals being killed went through the roof. The Japanese government issues annual quotas for how many small cetaceans may be taken, wih the total usually around 23,000 a year. Taiji doesn't have the biggest hunt - that honor goes to the killing of more than 15,000 Dall's porpoises in northern Japan - but it now certainly has the most infamous.

Taiji's changing demographics

Even more than Japan as a whole, the population of Taiji is growing older and in steady decline, dropping by about 10% per decade over the last 30 years. At the time of the last national census in 2005, it stood at about 3,500. Of this, a few hundred are thought to be employed from the drive fishery, with only a couple of dozen fishermen actually doing the hunting. There is little appetitie for the meat among younger people, particularly since it was taken off school lunch menus after two Taiji town councillors carried out tests that showed it was highly contaminated with mercury and other toxins. The drastic drop in the price of whale and especially dolphin meat means that the industry can only continue with the support of government subsidies...and the lucrative sale of captured dolphins to aquariums and dolphin encounters around the world. If Japan gets its way and is allowed to one day resume commercial whaling, there may be a resurgence of the industry in Taiji. But environmentalists would much prefer to see the town re-build itself around a new kind of relationship with whales and dolphins, one built on preservation and respect.

Related content